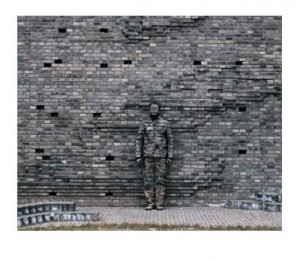

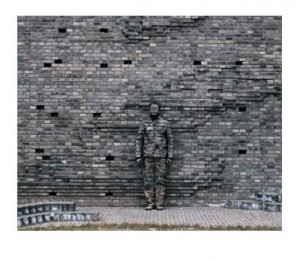

The invisibility of the artist Liu Bolin began with a simple action, intended as a passive mode of protest. When in 2005 his studio at the Suojia Village in Beijing was being demolished he photographed himself in front of it as a means of documentation. “On 17 November, the second day of demolition, I started to camouflage myself among the destroyed buildings of the campus. It was a way of protecting myself as an artist and, at the same time, of giving vent to my feelings. At that moment, the creation of my works constituted a sort of resistance against the decision made by the local government. My intention was one of rebellion. Not physical rebellion more of an attitude.“1

This action then evolved into a series of works, “Hiding in the City”, a kind of on-going performance having taken place so far in Beijing, Paris, the US, and Italy.

No. 63 Grays Opening Ceremony 2007, © Liu Bolin, provided by gallery photographerslimitededitions

The painting process, carried out by his assistants, can take up to 10 hours, leading finally to him almost disappearing into the respective background. And of course there are several layers of meaning behind this disappearance action: „Rather than saying that I disappear in the environment, it would be better to say that the environment has eaten me up and I cannot choose to be active or passive”, Liu Bolin comments. He approaches questions of being invisible to the society as an individual, the fear of perishing in the respective social environment, and he thus also scrutinises the relationship between the Self and the collective.

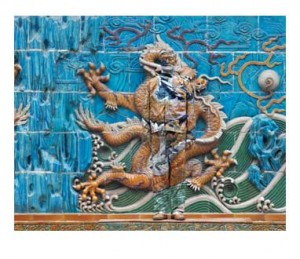

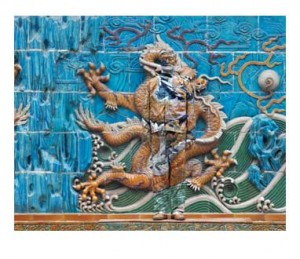

Dragon Series, © Liu Bolin, provided by gallery photographerslimitededitions

Another layer of interest lies in addressing the velocity of social, economic, and urban developments taking place and the disruptions these progressions may cause – for Liu Bolin these facts not only concern China but modern societies as a whole. “Even so, my position remains critical of the development of all humanity. We delude ourselves into thinking we are progressing, but actually it’s not like that at all. At the end of this development there will be the end of humanity, and I believe it will only take a few millennia. I know it’s a concept that’s hard to explain, but if we wonder: “What is the meaning of development?”, my answer is that development just doesn’t make sense.“2

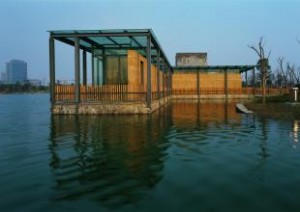

No. 04 Ground Zero 2011, © Liu Bolin, provided by gallery photographerslimitededitions

So, the concept behind Liu Bolin´s “Hiding in the City” is multilayered and very contemporary. And – as we art historians like to frame it – his images also work on the aesthetic level, meaning: they are beautiful to look at (also without knowing much about the background).

As he has also applied this conceptual approach within the “Lost in Fashion” series, in which he renders invisible popular fashion designers amongst their typical fabrics and patterns, the crucial question from an art critique´s point of view will be if he manages to develop his artistic concept any further within the coming years.

Gallery photographerslimitededitions Vienna, Bauernmarkt 14: Currently on show “Invisible Man Liu Bolin”, until 13th November 2012.

Further bits & images:

Galerie Paris-Beijing

Eli Klein Fine Arts, New York

boxart Gallery, Verona

1, 2 Artist´s statements in: “Liu Bolin in Italy”, Ed. by Fondazione FORMA per la Fotografia, Milano, 2010