The encounter of East and West has a long history of misunderstanding, conceit, oppression, romanticizing perspectives and sometimes mutual rejection. Among the many countries “east” China has always been an object of Western fantasies, aspirations and projections.

Despite several random encounters that happened more or less accidentally Chinese art and crafts became known in Europe initially through accounts of the Jesuit missionaries who arrived in Macao – a then Portuguese colony – during the first decades of the 16th century. Matteo Ricci, an Italian Jesuit, is one of the most well known missionaries and he became one of the first Western scholars to master Chinese script and language. The Jesuits sent back to Europe books including woodcuts and pictures, and the Portuguese started importing lacquers and porcelain, still often referred to as “China” of “Fine China”.

Matteo Ricci

At the very beginning of the 17th century, the Dutch together with the British East India Company broke the monopole and established their own trading systems from China to Europe – and as early as 1603 blue-and-white Chinese porcelain was appearing in Dutch paintings.

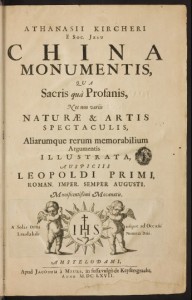

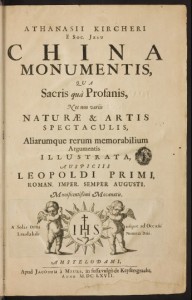

Athanasius Kircher, a 17th century German Jesuit, is another source of Western knowledge about China – although he himself had never been there. In 1667 he published an encyclopaedic book about China, known under the short title China Illustrata, in which he compiled material from other Jesuit´s or traveller´s reports containing a range of illustrating engravings. And lets also mention Joachim von Sandrart, a 17th century art historian active in Amsterdam, who in his Teutsche Academie talked among others about Chinese painting.

Athanasius Kircher: China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae and artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata

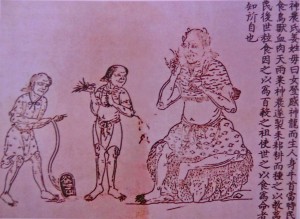

The point is that most of these missionaries and scholars very rarely have seen original Chinese paintings (much less did they appreciate these paintings as high art, but that will be dealt with in a separate post), most of the paintings or engravings circulating in Europe were a mixture of Chinese and Western elements and mostly a product of phantasy – produced mainly by the Jesuits and their scholars, repeating the same elements again and again in trying to comfort European taste.

Out of this fragmented knowledge about Chinese art, out of a longing for things exotic the Chinoiserie developed as a phenomenon mainly of the 17th and 18th century. This term is used for European decorative arts, crafts and designs that use Chinese motifs or styles and could be found almost everywhere: tapestries, wallpapers, textiles, vases and porcelain, furniture, lacquers, folding screens decorated in an allegedly Chinese style; cabinets and entire rooms painted with exotic motifs such as dragons, and fanciful sceneries; and pavilions, pagodas or tea houses in castle gardens built in a Chinoiserie manner.

François Boucher: Le Jardin chinois (detail)

C. Aubert: Engraving after a lost painting by Antione Watteau

The enthusiasm reached its height in the mid-18thcentury, when it so easily matched with the Rococo style. With the rise of Neo-Classicism in the European arts, Chinoiserie lost its importance.

Pagoda at Kew Garden

It has to be stressed that the basis for these use of Chinese-style motifs etc. lay not in genuine interest or in any form of appreciation of Chinese art. As already mentioned, Chinoiserie just satisfied a longing for things exotic and as there were no attempts for gaining a deeper understanding it was mostly based on superficial western concepts of things Chinese.

Michael Sullivan, in his wonderful book The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (which helped a lot in compiling this post) outlined this Western approach: “… that Chinoiserie has very little to do with China. The arrival of Chinese arts and crafts in the seventeenth century worked no transformation in French art; rather, the exotic imports were themselves transformed beyond recognition into something entirely French. Chinoiserie is, more than anything else, a part of the language of Rococo ornament. … nor did any European painter or critic in the eighteenth century say anything interesting or perceptive about them (i.e. Chinese paintings).”

The former notion of orientalism or exoticism has always been meant asymmetrically – that is with the West being superior in any aspect to whatever Eastern country. Traces of this conception can still be tracked down in current discussions in the context of globalisation within the art world – again, another topic for a separate post!

An interesting point is that Japonism manifested itself mainly within European painting whereas Chinoiserie were almost only to find in the decorative arts and crafts.

Further bits:

Chinoiserie (wikipedia).

Michael Sullivan´s wonderful book: The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (amazon).

Images used in this post:

Matteo Ricci from wikipedia.

Le Jardin chinois (detail) by François Boucher from wikipedia.

C. Aubert: Panel for the decoration for the Château de la Muette, engraving after a lost painting by Antoine Watteau taken from Sullivan´s The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art, p.101.

Pagoda at Kew Garden/London from wikipedia.