Juli 4, 2013

von admin

Keine Kommentare

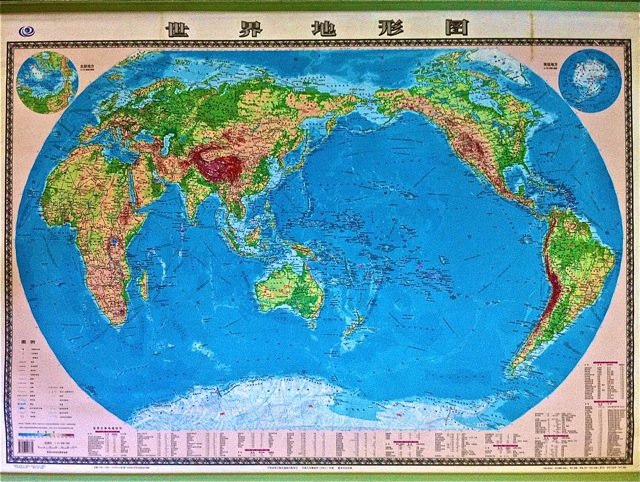

In China, the last decades with its dynamic developments brought with it many social trends, amongst it a movement from the countryside into the cities – young people looking for employment, for a better place to live, myriads of migrant workers.

What started at random, in the wake on ever increasing economy meanwhile turned into a political aim: Chinese prime minister, Li Keqiang, indicated at his inaugural news conference in March that urbanisation was one of his top priorities.

Ian Johnson describes this phenomenon in a recent contribution to the New York Times, “China’s Great Uprooting: Moving 250 Million Into Cities”: „China is pushing ahead with a sweeping plan to move 250 million rural residents into newly constructed towns and cities over the next dozen years — a transformative event that could set off a new wave of growth or saddle the country with problems for generations to come. The government, often by fiat, is replacing small rural homes with high-rises, paving over vast swaths of farmland and drastically altering the lives of rural dwellers. […] The ultimate goal of the government’s modernization plan is to fully integrate 70 per cent of the country’s population, or roughly 900 million people, into city living by 2025. […] In the early 1980s, about 80 per cent of Chinese lived in the countryside versus 47 per cent today, plus an additional 17 per cent that works in cities but is classified as rural. The idea is to speed up this process and achieve an urbanized China much faster than would occur organically.“

Ian Johnson describes this phenomenon in a recent contribution to the New York Times, “China’s Great Uprooting: Moving 250 Million Into Cities”: „China is pushing ahead with a sweeping plan to move 250 million rural residents into newly constructed towns and cities over the next dozen years — a transformative event that could set off a new wave of growth or saddle the country with problems for generations to come. The government, often by fiat, is replacing small rural homes with high-rises, paving over vast swaths of farmland and drastically altering the lives of rural dwellers. […] The ultimate goal of the government’s modernization plan is to fully integrate 70 per cent of the country’s population, or roughly 900 million people, into city living by 2025. […] In the early 1980s, about 80 per cent of Chinese lived in the countryside versus 47 per cent today, plus an additional 17 per cent that works in cities but is classified as rural. The idea is to speed up this process and achieve an urbanized China much faster than would occur organically.“

Many aspects to think about, among the critical ones:

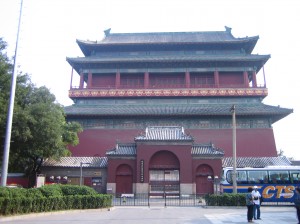

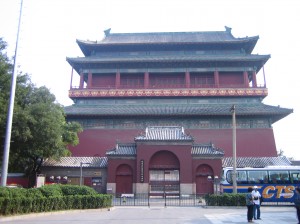

Destruction of farmland, changes in social structures and life-style, loss of some cultural heritage witnessing traditional Chinese culture and way of life (one of the recent examples is located not in the countryside, but in Beijing, the stepwise destruction of the quarter around both the Bell and Drum Tower), or potential of creating a permanent underclass in big Chinese cities.

On the other side urbanization is generally regarded as one of the manifold manifestations of modernity. It represents for example a higher economic standard or a lifestyle less bound to traditional and thus mostly narrower notions. These developments reflect a process that has long since started in the Western hemisphere. Last not least, a continuously consuming city dweller is essential for keeping up economical numbers.

I am one of the last ones with a pseudo-romantic view upon old structures – an attitude foreigners and visitors to Beijing like to display when longing for “authentic” impressions during their trips. How many of them would really want to live in an undeveloped area without any functioning system of electricity or sewerage?

But between white and black there are many shades. Urbanity does not mean just as many people as possible living in high-rise buildings – it is something that develops gradually, together with changes in lifestyle and mentality, it is about new possibilities, about more education, it is also an attitude.

But between white and black there are many shades. Urbanity does not mean just as many people as possible living in high-rise buildings – it is something that develops gradually, together with changes in lifestyle and mentality, it is about new possibilities, about more education, it is also an attitude.

What it is then that is criticised really? Maybe the velocity, maybe the slight unease at a central government that decides for so many people where to continue their life, or maybe just envy of the old world at the dynamics somewhere else in the world…

Further bits:

Ian Johnson: China’s Great Uprooting: Moving 250 Million Into Cities, The New York Times.

Tom Miller: China’s Urban Billion: The Story Behind the Biggest Migration in Human History (amazon).

Dagongmei Working Sisters, post on urban migrant workers.