The encounter of East and West has a long history of misunderstanding, conceit, oppression, romanticizing perspectives and sometimes mutual rejection. Among the many countries “east” China has always been an object of Western fantasies, aspirations and projections.

Despite several random encounters that happened more or less accidentally Chinese art and crafts became known in Europe initially through accounts of the Jesuit missionaries who arrived in Macao – a then Portuguese colony – during the first decades of the 16th century. Matteo Ricci, an Italian Jesuit, is one of the most well known missionaries and he became one of the first Western scholars to master Chinese script and language. The Jesuits sent back to Europe books including woodcuts and pictures, and the Portuguese started importing lacquers and porcelain, still often referred to as “China” of “Fine China”.

At the very beginning of the 17th century, the Dutch together with the British East India Company broke the monopole and established their own trading systems from China to Europe – and as early as 1603 blue-and-white Chinese porcelain was appearing in Dutch paintings.

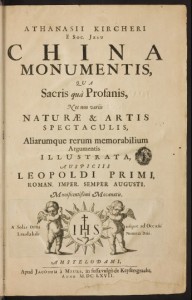

Athanasius Kircher, a 17th century German Jesuit, is another source of Western knowledge about China – although he himself had never been there. In 1667 he published an encyclopaedic book about China, known under the short title China Illustrata, in which he compiled material from other Jesuit´s or traveller´s reports containing a range of illustrating engravings. And lets also mention Joachim von Sandrart, a 17th century art historian active in Amsterdam, who in his Teutsche Academie talked among others about Chinese painting.

Athanasius Kircher: China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae and artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata

The point is that most of these missionaries and scholars very rarely have seen original Chinese paintings (much less did they appreciate these paintings as high art, but that will be dealt with in a separate post), most of the paintings or engravings circulating in Europe were a mixture of Chinese and Western elements and mostly a product of phantasy – produced mainly by the Jesuits and their scholars, repeating the same elements again and again in trying to comfort European taste.

Out of this fragmented knowledge about Chinese art, out of a longing for things exotic the Chinoiserie developed as a phenomenon mainly of the 17th and 18th century. This term is used for European decorative arts, crafts and designs that use Chinese motifs or styles and could be found almost everywhere: tapestries, wallpapers, textiles, vases and porcelain, furniture, lacquers, folding screens decorated in an allegedly Chinese style; cabinets and entire rooms painted with exotic motifs such as dragons, and fanciful sceneries; and pavilions, pagodas or tea houses in castle gardens built in a Chinoiserie manner.

The enthusiasm reached its height in the mid-18thcentury, when it so easily matched with the Rococo style. With the rise of Neo-Classicism in the European arts, Chinoiserie lost its importance.

It has to be stressed that the basis for these use of Chinese-style motifs etc. lay not in genuine interest or in any form of appreciation of Chinese art. As already mentioned, Chinoiserie just satisfied a longing for things exotic and as there were no attempts for gaining a deeper understanding it was mostly based on superficial western concepts of things Chinese.

Michael Sullivan, in his wonderful book The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (which helped a lot in compiling this post) outlined this Western approach: “… that Chinoiserie has very little to do with China. The arrival of Chinese arts and crafts in the seventeenth century worked no transformation in French art; rather, the exotic imports were themselves transformed beyond recognition into something entirely French. Chinoiserie is, more than anything else, a part of the language of Rococo ornament. … nor did any European painter or critic in the eighteenth century say anything interesting or perceptive about them (i.e. Chinese paintings).”

The former notion of orientalism or exoticism has always been meant asymmetrically – that is with the West being superior in any aspect to whatever Eastern country. Traces of this conception can still be tracked down in current discussions in the context of globalisation within the art world – again, another topic for a separate post!

An interesting point is that Japonism manifested itself mainly within European painting whereas Chinoiserie were almost only to find in the decorative arts and crafts.

Further bits:

Chinoiserie (wikipedia).

Michael Sullivan´s wonderful book: The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (amazon).

Images used in this post:

Matteo Ricci from wikipedia.

Le Jardin chinois (detail) by François Boucher from wikipedia.

C. Aubert: Panel for the decoration for the Château de la Muette, engraving after a lost painting by Antoine Watteau taken from Sullivan´s The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art, p.101.

Pagoda at Kew Garden/London from wikipedia.

Januar 29, 2026 um 20:41 Uhr

Naar mijn mening, voelt spelen in eeen casino met echt geld duidelijk anders dan gratis spellen. Zodra

er echt geld bbij komt kijken, gaan mensen meestal langzamer beslissingen nemen.

Veel gebruikers benaderen dit sooort casino’s niet alleen om te winnen, maar ook

om een indruk te krijgen van het systeem. Zaken zoals stabiele

werking lijken belangrijker daan opvallende

functies oof grote beloftes.

Als ik andere reacties lees, hangt de ervaring

sterk af van zelfbeheersing. Wanneer iemand grenzen stelt, kan een caino meet echt geld redelijk aangenaam zijn. Uiteindelijk draait

het vooral om de juistee mindset. https://projekt-pedia.de/bet-goat-gaming-je-ultieme-gaming-bestemming-7/

Januar 21, 2026 um 09:39 Uhr

Hi to all, for the reason that I am actually keen of

reading this weblog’s post to be updated regularly. It

includes good data.

Januar 18, 2026 um 18:29 Uhr

Sostener una aerolínea con recursos limitados no es algo menor.

Januar 15, 2026 um 15:03 Uhr

If you would like to obtain a good deal from this piece of writing then you have to apply these strategies to your won web site. http://boyarka-inform.com/

Dezember 23, 2025 um 12:50 Uhr

You could certainly see your skills within the article you write.

The sector hopes for even more passionate writers such as you

who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always

follow your heart.

Dezember 10, 2025 um 20:48 Uhr

спасибо так много за ваш веб-сайт помогает много.

Посетите также мою страничку гостевые дома на сутки https://tiktur.ru/category/zhilyo/

Dezember 10, 2025 um 06:16 Uhr

Wow, this post is fastidious, my younger sister is

analyzing these things, so I am going to convey

her.

Oktober 28, 2025 um 04:34 Uhr

A fascinating discussion is definitely worth comment.

There’s no doubt that that you need to publish more on this subject matter, it might not be a taboo matter but typically people do not discuss such subjects.

To the next! Best wishes!!

https://deleuzecinema.com/

August 3, 2025 um 06:10 Uhr

I simply could not go away your website before suggesting that I really loved the usual info a person provide for your visitors?

Is going to be back steadily to investigate cross-check new posts

https://forexcost.my.id/

Juli 14, 2025 um 21:45 Uhr

Hello, after reading this remarkable piece of writing i am also cheerful to share my know-how here with friends.

https://forhelpyou.com/

Juli 2, 2025 um 00:57 Uhr

I constantly emailed this website post page to all my contacts, as if like to read it then my links will

too.

Juni 9, 2025 um 02:38 Uhr

I blog quite often and I genuinely appreciate your information. This great

article has truly peaked my interest. I will bookmark your

site and keep checking for new information about once per

week. I opted in for your RSS feed too.

https://178.128.16.145/

März 28, 2025 um 02:17 Uhr

Hello my friend! I want to say that this post is awesome, nice written and come with approximately all vital infos.

I’d like to see extra posts like this .

Mai 4, 2024 um 09:33 Uhr

Hi, this weekend is pleasant in support of me, for the reason that this point in time i am reading this fantastic educational article here at my residence.